Betraying the Savarna voters, the BJP announced on 30th April that it would be conducting a nationwide caste census. The news has come as a blow to the upper castes. They now fear the impact that the caste census would have on their lives. While the timeline and structure have not been decided, Bihar might be the first state to test the political impact of the Centre’s caste census.

The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of the Caste Census.

The last nationwide Caste Census in India took place in 1931. The one that took place in post-independent India in 1951 was only for SCs and STs because the leaders feared that it might disrupt the unity of Hindus.

Caste census is basically the collection of caste identities that are accumulated during the national census. Since India is a highly caste-dominated country, the caste census will dive deeper into socio-economic status of different castes.

Although India conducted socio-economic caste census (SECC) in 2011, the findings were not publicised due to the fears of division. However, the vote politics, current demands (and of course the unnecessary bullying of the opposition) led the present regime to decide to add the caste enumeration in their policies.

While there are a multitude of issues with conducting a caste census, especially when the news was dropped during such turbulent times when our nation is already suffering from the aftermath of the Pahalgam attack, it has its own social and economic implications. The data collected under the caste census influences the policy formation and resource allocation. In various sectors – healthcare, medicine, education, and ration, the distribution under welfare schemes is done on a caste basis. Hence, the data helps in even and proper allocation. The supporters debate that the old data is out-dated and new findings are required for better representation and distribution.

‘The Upper Castes’ Against the Caste Census

Post ‘Mandal Commission’ implementation in the 1990s, we have seen upper caste protests, with some even resorting to extreme measures. Students burning themselves on fire, clashes and unrest started to take violent turns among students, who mainly were from middle-class urban areas. Mandal Commission recommended 27% reservation for OBC, on socio and economic basis. Students feared that it would dilute the meritocracy and thus their chances at jobs and education.

Since the current government has announced the caste census enumeration in their policy, new criticisms have emerged. On the other hand, opposition is ‘riding on BJP’s coattails’ thinking that it was their ‘constant pressurising’ that gave way to this decision, knowing fully well that it was actually a step towards vote bank politics.

The nationwide caste census would dig deeper into the caste divisions, commencing from the Bihar caste census. It will highlight the need for increasing the OBC reservation proportionate to their population.

The predicted increased OBC reservation would create turmoil and would lead to further unrest. Already, the reservation narrative in India is suffering from a negative image nationally and even internationally.

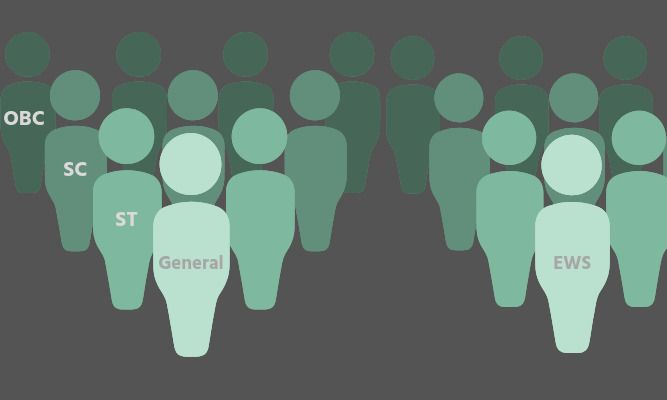

Under the Indra Sawhney judgement, given by the Supreme Court, the bench set the 50% cap on the reservation. This was done to safeguard the rights of the general category after ‘V.P Singh’s government’ implemented the recommendations by the Mandal Commission, which were subsequently challenged in the apex court. The bifurcation of the current reservation system is mentioned in the table given below.

| SC | 15% |

| ST | 7.5% |

| OBC | 27% |

| EWS | 10% |

Despite the 50% cap set by the Supreme Court, some of the states have already crossed the threshold. There is a 75% reservation in Bihar, where the caste based discrimination has always been a major hindrance to development.

The ‘Caste Card’ As An Indian Political Tool

The current political scenario reminds me of what Dr BR Ambedkar said about the permanence of caste and reservation.

“You cannot build anything on the foundation of caste. You cannot build up a nation; you cannot build up a morality. Anything that you will build on the foundations of caste will crack, and will never be a whole.”

The leaders in positions of power failed to interpret the deeper meaning behind his words and ended up using the caste as a political tool. Using the ‘caste card’, the parties mobilise voters and even form alliances with each other. They align themselves with certain castes and work only for the fulfilment for that particular section excluding others. This idea reinforces the division between the castes instead of annihilation, which was the actual dream of Dr BR Ambedkar.

States like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, with their maximum caste diversity, become vulnerable to this dirty vote bank politics.

BJP’s years-old ideology of uniting the castes came to a sudden halt when the PM announced the nationwide caste census. The decision might be influenced from the previous losses that BJP had to suffer due to negligence of castes.

Another reason that may have swayed this decision is the emergence of the coalition government in 2024. This was an unfortunate development for the BJP, especially in its third tenure, because it affected decision-making and the coalition required appeasing everyone. It has clearly pushed the party leadership to acclimate to the idea of prioritising caste, particularly in states like Bihar, with elections now approaching.

Whatever the reason may be, evidently BJP’s ideal of ‘katoge toh batoge’ has been left behind, now that they have held onto ‘jiski jitni sankhya bhaari utni uski hissedari’ because, after all, it’s all about vote bank fulfilment.

Levelling The Playing Field Via The Caste Census

Unfortunately, denying the existence of the caste does not eradicate the crimes that are still committed against the lower castes. Even in this decade, when we have seen the boom in technology, reached the southern part of the moon, the same society has also witnessed a section that is forced to indulge in manual scavenging.

Caste based discrimination is one of the major factors that affects our development. While it is easy to criticise the ever-increasing reservation, not enough steps are taken eradicate the problem of caste. We still read about Dalit students being discriminated in schools. Lower castes women become victim to some barbaric upper castes men, raped and killed. As long as there is even one case, the right to berate reservation and even the caste census shouldn’t exist.

Conclusion

I am not sure whether caste census is the solution; mostly it is the vote bank politics. However, there is a need for deep reforms with utmost urgency to address the problem of caste discrimination. Caste, if it must exist, must remain a fluid identity because rigidity only deepens societal issues. Certain caste identities must not be synonymous with hierarchies creating distinctions between different sections. The Caste Census may or may not entrench the caste identities deeper, creating a new set of problems.

The current reservation system is highly problematic. The system benefits mostly the ‘creamy layer’, Who are anyway the better-off within the reserved categories. There’s no periodic review of who needs it and who doesn’t. Many groups may no longer be as disadvantaged, while others (like some EWS groups) are left out or underrepresented.

While the Caste census may be the right choice for the development of castes, its productivity would be void because it will be used to divide people further in the name of party alliance. If the party’s sole focus is on identity, it will only divide the country rather than unite it.

Pingback: Waqf Law And Women : Representation or Representation Politics? - V&V

Pingback: Waqf Amendment 2025 In Supreme Court: Legal Heat Explained - V&V